A lot has happened on the Korean peninsula in the last few weeks. South Korean president Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un met for the first time; Kim took some serious steps toward denuclearization; and Kim and President Trump agreed to talk, but Trump abruptly canceled the historic meeting. On June 1, however, following a meeting with a high ranking North Korean official, President Trump announced that he plans to meet Kim Jong-un.

I watched these events unfold with interest since two months earlier, I had traveled to South Korea with 12 journalism students to report on ongoing religious, political and cultural developments.

When we landed at Seoul’s Incheon Airport, the warm diplomatic tailwinds of the Winter Olympics had thawed relations between the North and South. Kim and Moon would soon meet. And there were rumors of a Trump and Kim parlay to follow.

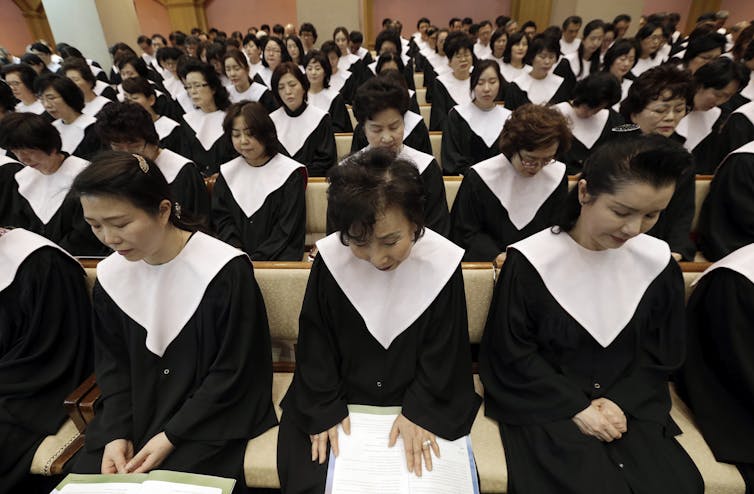

My students had many questions about the role of religion in the land of K-pop, including Christianity’s involvement in either promoting or preventing improved relations between the North and South. Even though half of all South Koreans are religiously unaffiliated, Christianity has had an outsized influence in the country. Many of the world’s largest churches are located there, and many South Korean political and business leaders are staunch Christians.

Korean Christianity

For the first half of the 20th century, Christianity gained little ground in Korea. Confucianism, Buddhism and shamanism persisted despite efforts of Protestant and Roman Catholic missionaries. But after the Korean War, the country’s religious landscape changed dramatically.

Communists in the North banned most Christian practice, replacing traditional beliefs and rituals with Juche, an official state ideology that mixes Marxism and self-reliance with veneration for Kim Il-Sung, the nation’s first leader.

The South’s experience could not have been more different.

American support for the fight against Communism and its aid in postwar reconstruction boosted Christianity’s popularity. That’s because Christianity was the Americans’ religion, and many South Koreans wanted what America had – wealth, freedom and “divine blessings.”

Conversions soared and among the most successful churches were those espousing values similar to Confucianism, the Chinese philosophy that migrated to Korea some 1800 years ago, and is deeply embedded in its culture. Both Confucianism and conservative Christianity emphasize traditional gender roles, strong families, and respect for authority.

Today, almost 30 percent of the country is either Protestant or Roman Catholic, with conservative evangelicals playing a significant role in the nation’s politics and culture.

Large Korean megachurches, like their American counterparts, tend to be pro-democracy, pro-free market and anti-communist. They support U.S policy and, like many evangelical and “prosperity” churches in the U.S., believe that Donald Trump is God’s man.

During our visit, we found that many Korean Christians are wary of Kim’s overtures to Moon, including talk of reconciliation. Their preference is reunification: one democratic country where Christianity is openly practiced.

Reunification not reconciliation

Indeed after the Korean War, many South Koreans yearned for a reunited nation. Many had relatives in the North and could not imagine a permanent separation.

While many of these older Koreans still want to see the two countries reunited, young people do not share the sentiment.

In 2017, the government’s Institute for National Unification found that 71.2 percent of 20-something South Koreans oppose reunification. For the time being, however, young folks are a minority. So today, about 58 percent of the population does favor a reunited peninsula, but their numbers are falling.

Younger Koreans have pragmatic as well as ideological reasons for opposing reunification. North Korea is a poor, totalitarian state. South Korea is a wealthy, democratic one. The political difficulties of bridging the difference seem insurmountable, especially with Kim in power. The economic challenge is equally daunting. South Koreans have worked hard for success and many do not want to jeopardize their high standard of living to help their “poor cousins” in the North.

But President Moon Jae-in, the son of North Korean refugees, has his own ideas about reconciliation and reunification. Unlike his conservative predecessor, Park Geun-hye, who was impeached and sentenced to prison for abuse of power and corruption, Moon is a former human rights attorney. He is willing to start with reconciliation, but his long-term goal is a united peninsula.

Action on the ground

While Moon Jae-in, Kim Jong-Un and Trump conduct a complicated diplomatic dance, religiously based, grassroots initiatives take small steps forward. For some, this means sending messages over the border, for others it’s helping defectors adjust to the South, and for still others, it involves paving the way for reunification.

Staff at Far East Broadcasting System’s Seoul office focus on evangelizing North Korea. They smuggle radios into the Communist-controlled country so citizens can listen to sermons, services and shows about Christianity. The station also broadcasts in South Korea, where its content includes information on reunification.

“We just want to share the Christian gospel,” Chung Soo Kim, a staff member, told one of my students. Kim added that North Korean attempts to stop the programming have failed: “They cannot afford to jam our broadcasts. They do not even have enough food to feed their people.”

Other Korean Christians assist North Koreans who have defected. There are about 31,000 defectors in South Korea, and many have trouble adjusting to their changed circumstances. The South Korean government provides some help, but clergy and churches try to fill in the gaps. According to some defectors, religion helps with acculturation.

The Rev. Chun Ki Won, for example, started Durihana International School in Seoul as an alternative for young North Koreans, whose foreign accents and hand-me-down clothes make them targets of ridicule in South Korean schools.

“I realized after rescuing North Korean defectors from China and leading them to South Korea that they don’t settle down properly,” Chun told a student through a translator. “We teach them the purpose of their lives and their identity. We teach them why God made them to suffer, and that there is purpose in that.”

One of the more ambitious programs aimed at reunification is River of Life, a school run by Ben Torrey, grandson of a famous 19th century American evangelist, Reuben A. Torrey. Ben Torrey integrates reunification into the curriculum for Korean Christian children.

Torrey’s students meet with defectors and, building on personal relationships, slowly embrace the idea of one Korea. Jin-soo (his first name), one of Torrey’s students told my student through a translator: “I went to a public elementary and middle school. In that school, at least once a year, we talked about reunification, but it was just something in the textbook, nothing that comes alive.” He explained how things changed once he had a chance to meet North Korean students. “I began thinking from their perspective,” he said. “They are the same as I am.”

Like Torrey, Korean Christians who support reunification see it as a political and religious goal. And although it’s an uphill struggle, they believe with faith anything is possible.

In fact, that’s the takeaway that struck several in my class: The faith of many Korean Christians supersedes political calculation. Or, as Ben Torrey told one of the students about a united peninsula,

“God has to do it. It has to be a miracle.”

This piece, first published on June 1, was slightly updated to reflect the latest developments on North Korea.

Diane Winston, Associate Professor and Knight Center Chair in Media & Religion, University of Southern California, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.