The recent killing of a 26-year-old U.S. missionary, John Allen Chau, on a remote island in India has raised many questions about global evangelical Protestant missions.

Chau was on a personal mission to convert the Sentinelese, a protected tribe who have avoided contact with the rest of the world. Indian ships monitor the waters to stop outsiders from approaching them. Chau, however, is reported to have asked fishermen to take him illegally to the island where the Sentinelese live. The Sentinelese are reported to have shot and killed him with arrows.

As my research on missionaries shows, this often unwise haste to evangelize the world was the founding characteristic of evangelical missions in the late 19th century.

Faith missions

From the beginning of the 19th century, Protestants sent missionaries abroad under mission boards that required seminary education and full funding for prospective recruits. By the end of the 19th century, however, some mission leaders believed that the established missions were evangelizing the world at much too slow a pace.

Evangelicals believe in a hell where the souls of those who don’t convert to Christianity will burn forever.

Missionaries are motivated by Christ’s words in the “Great Commission” to “make disciples of all nations.” In these biblical verses, the risen Christ commands his disciples to go into all the world and preach the gospel. This command has motivated the missionary enterprise for centuries.

These leaders founded what became known as “faith” missions to greatly expand the missionary force. As I write in my book, the new missions began sending out highly committed but lightly educated and ill-prepared missionaries. Many had not even finished high school. Just a bit of Bible training was considered enough.

There were dozens of such missions by the early 20th century, each founded to Christianize a specific section of the globe, such as the China Inland Mission, the Sudan Interior Mission and the Central American Mission.

Hundreds of young men and women, often with families, were sent overseas with little to no training in anything beyond the Bible and no promise of funding.

While doing archival research for my book, I also found evidence of the conversations between the missionary leaders and their young recruits. The first question, for example, R. D. Smith, a leader of the Central American Mission, posed to new recruits:

“Do you understand that you are to trust the Lord for the supply of all your needs and not rely upon the Central American Mission or any other human agency?”

He did not want new recruits to even have one year’s funding in place. “I am not exercising faith,” Smith groused, “if I have a year’s supply in hand.”

In digging into records in the Townsend archives in Waxhaw, North Carolina, I also found that recruits were told simply to pray, and God would provide the necessary funds: hence the name “faith missions.”

These records show that mission leaders believed such a plan would result in a more “spiritual” missionary force, as missionaries were forced to rely only on God for their needs. Cameron Townsend, a Central American Mission recruit, wrote in 1927: “We want entire dependence on God, and not on anyone’s bank account.”

Missionary zeal

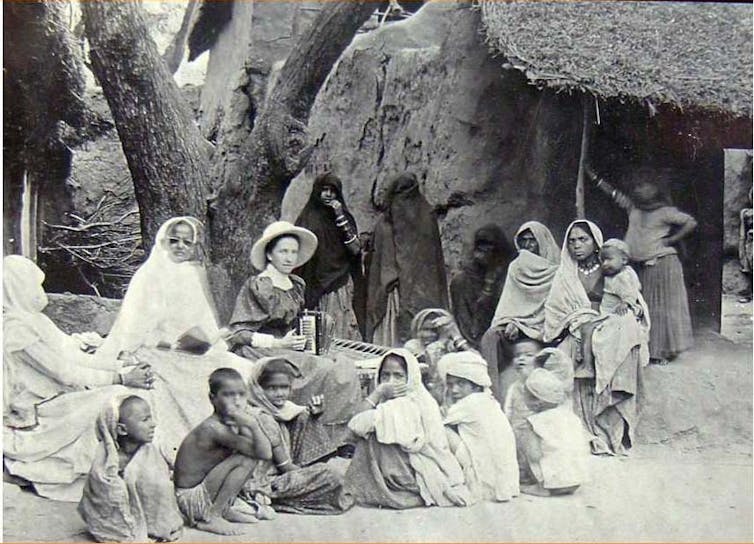

Unknown photographer via Wikimedia Commons

Hundreds of untrained, unfunded, largely unsupervised young people got on boats to Africa or Asia knowing little about where they were going and with no language training other than what they might pick up from the missionary in the cabin next door.

That tragedy often resulted should come as no surprise. A. T. Pierson, an early promoter of faith missions, argued to the leaders of the Africa Inland Mission in the late 1890s, after all of the initial 16 recruits the mission sent to Africa either died or quit,

“The hallmark of God on any work is death. God has given us that hallmark. Now is the time to go forward.”

While no official estimates are available, the death of missionaries was accepted as a common occurrence. The board of directors of an evangelical mission, the Nazarene Missions International, once sent a letter to two of its sick missionaries saying “we presume you will already be dead,” to explain why no funds were sent for the month – perhaps referring to funds that came through family or friends.

In this case, the missionaries recovered. But how long they survived afterwards is not clear.

Linguistic training

By the 1930s some mission leaders were recognizing that such a plan was untenable.

The Wycliffe Bible Translators, the largest and most influential faith mission in the 20th century, founded by Cameron Townsend, who had earlier advocated for dependence on God, began providing its recruits with much more thorough training and support. This included linguistic training through its Summer Institute of Linguistics.

The goal was to teach missionaries how to, first, learn languages that had never been written down and second, create a written language. The ultimate goal was to translate the Bible into every language in the world. By midcentury these linguistic training institutes were recognized on secular university campuses as ranking with the best in the world. My own parents spent 30 years with Wycliffe translating the Bible into the Mansaka language in the jungles of the Philippines, where I grew up.

At the same time, many of the Bible institutes, which had sent many graduates to the faith missions, were becoming Bible colleges and universities, and missionary training was becoming more thorough and academic.

The discipline of anthropology made inroads into evangelical colleges by the 1960s and dramatically changed missionary education.

Today’s evangelizing

Most evangelical missionaries today are at least college-educated, and many have graduate degrees in anthropology or linguistics. John Allen Chau was a college graduate who had briefly attended a Canadian linguistic institute affiliated with Wycliffe’s Summer Institute of Linguistics, but he was not trained to be a missionary. He had majored in sports medicine.

And while evangelicals continue to send missionaries as educators or business people to places where proselytizing is not welcome, such as China, few established missions today would sponsor Chau’s amateurish and obviously illegal approach.

Today’s missions understand that passionate faith like Chau’s is not enough.![]()

William Svelmoe, Professor of History, Saint Mary’s College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.